The Martian Annotated Bibliography

Weir, Andy. The Martian: A Novel. New York: Crown, 2014. Print.

Robert Finch

The Martian is a piece that divided our group as an audience. Many of us found us found it far from an easy read, and were resistant readers, while I (Robert Finch, the writer of this section) found that the book was standard science fiction and thus I felt at home with the format. My goal throughout this document is to bring together my group’s collectives thoughts on the Martian as to build upon the analysis to delve into the four subjects assigned to our group, namely the “Reading for” or mimetic and thematic reading, the structure of the piece from the various forms (eg repetitive form), the intertextual codes, and finally an analysis of the narrative intentions of the author to his audience.

Section 1

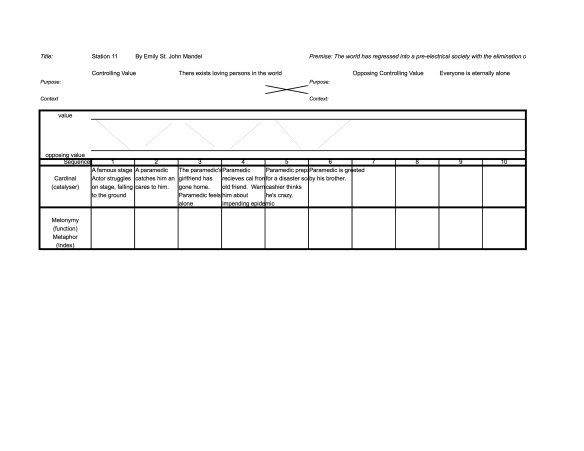

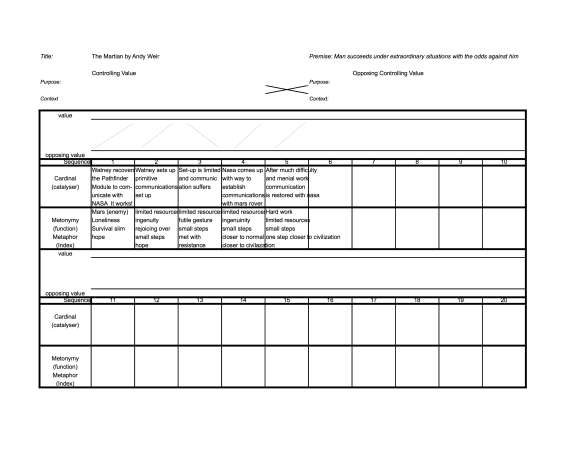

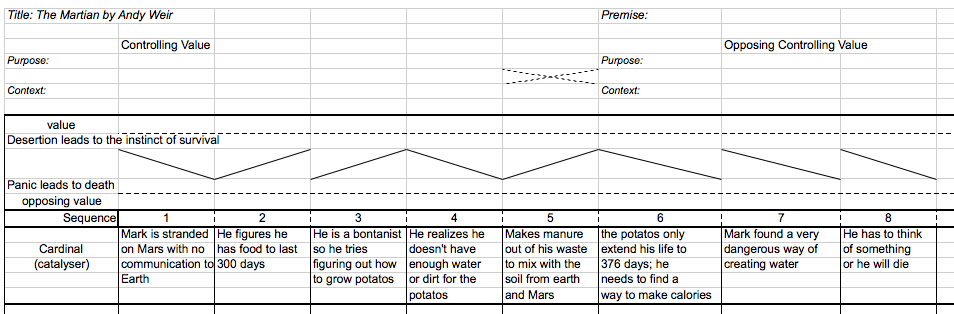

The Martian, a book by Andy Weir, is a novel which in the mimetic register details an aborted human study of the Mars planet where Mark Whatney, one of the astronauts, becomes stranded on the planet with material designed to last several weeks at most. His only choice is make-do with what he has to survive until the next manned-mission can picked him up, at the very least in several years. It’s a race against time as NASA struggles to reduce that time-frame and Whatney struggles to grow food and survive in a hostile environment. Thematically Alexis and I agreed in our value graph that his predicament saddled Mark Whatney with an “instinct to survive” and that the controlling value is whether his fortitude will result in his living out the rest of his natural life.

The Value Graph is from the first three chapters of the book, where Mark is figuring out ways of creating food and surviving while being stuck on Mars.

This story is as many in our group described it a “science-fiction” novel. According to the Free Dictionary a “science-fiction novel” is “A literary or cinematic genre in which fantasy, typically based on speculative scientific discoveries or developments, environmental changes, space travel, or life on other planets, forms part of the plot or background. “ The Martian does fit this category, taking it upon itself to describe potential future technology that humanity (particularly NASA) will use to explore Mars via a manned mission

It was this particular aspect that created resistant readers out of my groupmates in their initial reading-fors (As well as throughout their reading experience). As Alexis states

“Throughout the first few chapters, I felt myself resisting the text, like when he was explaining how to separate hydrogen from hydrazine or how the equipment and supplies that he was using or wearing worked, like the MAV or his space suit. “

And for Laura

“As I continued to read on I noticed, I was not quite a resistant reader to the text, but more along the lines of an inauthentic submissive reader. I was mechanically going through each paragraph and then realizing I was not paying attention to the words on the page. “

The very subject matter, the science-fiction element, alienated many of us, from Alexis’s stated difficulty reading the scientific passages to Laura simply not connecting with the scenario.

However there was another aspect that did come up during our reading-for’s, and that was a feeling of a “survival story” aspect. As Brittany states

“Reading deeper into the book, I begin to think that it maybe more then just a science fiction book and maybe a book about a fight for survival.“

This consensus was shared by all of my group mates (with the exception of me) in regards to the idea that a Science-Fiction novel would involve something more than simply a man on mars trying to create the world’s first martian grown potatoes. In fact many of our group’s submissive reading followed when we see Mark Whatney’s emotions as he fails and succeeds in his attempt to survive. According to Laura

“Other times while reading, I felt as if I were becoming a submissive reader and allowing the text to work it’s magic on me. I was open to the narrator showing me the ways of which he was going to survive Mars with only a maximum of 300 days food. When he states, “Okay, I’ve had a good night’s sleep, and things don’t seem as hopeless as they did yesterday” (23). I can put myself into his shoes without being on Mars. I can feel him panicking the night before and falling asleep to some glimpse of hope to survive. “

As for my own reading-for, with my strong interest in Science-fiction I was submissive in different parts than my groupmates. I actually enjoyed the technical talk while much of Mart Whatney talking about his worries actually grew tired in my personal opinion since it felt repetitive. But that’s more of a subject to tackle in a future section on cultural codes, since the cultural codes I’m used to seeking are different than those of my groupmates who didn’t have much experience in science-fiction.

Section 2

The Martian in terms of Form had a very specific style.

In terms of Syllogistic progression the Martian often brings forth these Premises. That Mark Whatney has suffered a major setback (I.E. his potato farm has failed) he mopes about it, feeling as if he’s about to die. And then he realizes that all isn’t hopeless “Well, I didn’t die” (51) He decides that he isn’t going to die, finds a solution to the problem.

Often during this strategy Qualitative progressive form is used. During Whatney’s journal entries in which he addresses the audience he often uses jokes and dry humor to convince him “I am one lucky son of a bitch [the potatoes] aren’t freeze-dried or mulched” and through this griping we laugh along with Whatney laughing at himself.

In true repetitive form disasters happen over and over again, and as these occur Whatney thinks, panics, and then resolves the issue.

In terms of genre and in terms of defining it, my groupmates and I had very different expectations and understandings. We agreed, the genre of The Martian was Science-fiction, but what we expected and saw the genre as was entirely different. Case in point, a quote by Alexis

“During the first reading, my initial reading for was the science fiction elements that are prevalent in sci-fi…but it surprised me to find out that it also seems to be more about the survival story of the main character, Mark.”

And then again coming up in Laura’s entry

“I started to see that maybe there is more to the genre than just science-fiction. This could be a story about Mark’s survival….This text might be dealing with the certain ways we must survive in a bigger genre [than] science-fiction.”

As these readers indicate, rather than what is commonly accepted as aspects of the genre (Ex. Epic space battles, future societies, alien beings) we have elements of survival fiction in here where the story focuses primarily on the survival of one man in the inhospitable environment of Mars.

But as we remember from section one, The Free Dictionary says science-fiction is

“A literary or cinematic genre in which fantasy, typically based on speculative scientific discoveries or developments, environmental changes, space travel, or life on other planets, forms part of the plot or background.”

As Laura states

“As I was reading, I started to notice that, yes, there is a lot of scientific information in the novel.”

and thus we have that quality down, that the book does focus on the science element.

To quote Laura’s quoting the text

“Hydrazine breaking down is extremely exothermic. So I did it a bit at a time, constantly watching the readout of a thermocouple I’d attached to the iridium chamber” (53).

referring of course to Mark Whatney’s effort to introduce water into the soil by burning rocket fuel (the Hydrazine). She explores this issue further in saying

“I started to see that maybe there is more to the genre than just science-fiction. This could be a story about Mark’s survival. “

In other words she noticed that her perception of the genre “science-fiction” was simply not the same as the text of The Martian was delivering.

This calls for a definition of the “Survival” genre. Book-Genres.com describes the survival fiction genre as

“… made up of stories where the main character or characters are trying to survive with little or nothing… who have gotten lost or hurt in a natural environment and have to survive on their own until rescued. The main theme… is the knowledge and how-to to make do with what one has in a limited environment and keep themselves and/or others alive.”

Concerning The Martian this is a very adequate description. Mark Whatney is stranded in a “natural environment” (you can certainly say that Mars is “natural” and he has to “make do” with materials he has on hand. Yet when you compare The Martian with other survival stories like…say the movie Cast Away, you realize that not only is the setting different (Cast Away takes place on an uninhabited island) but there is an element that simply isn’t there…namely the science!

Mark Whatney, our protagonist, is always explaining himself and his methods (see the early quote about the Hydrazine) and the fact that even manned travel to Mars is futeristic, many of the methods described in The Martian are simply hypothetical even if they are based on current science. While survival stories often take place in modern or past environments, The Martian takes place in a hypothetical future where this technology has been developed and is in use. Thus although we can state that the novel does have survival genre elements, the environment is not some frozen wilderness or an island but on a planet that as of this date mankind has never even set foot on personally. Thus the definition of “typically based on speculative scientific discoveries or developments, environmental changes, space travel, or life on other planets, forms part of the plot or background.” is more defined here despite many in my group feeling that the survival elements place it in a different genre.

Section 3

Moving on from a discussion on genre we have the “intertextual code” or otherwise the question “how does this book relate to other texts?” or “ what outside sources or experiences can we use as a reference to better understand this book?” We have the genre, that being that The Martian is a Science-Fiction story with Survival story elements, but what does that tell us? It tells us the playground that Andy Weir, the author of The Martian is playing with in that genre narrows down the type messages and stories he can tell within his chosen genre. But now we dig deeper, what is Andy Weir trying to convey?

We of course know the structure of the story. Alexis, in her entry on the matter, writes on the proairetic code,

“From what I have read, there have been times when he finds ways of surviving, like when he figures out how to grow potatoes and make water while being stranded on Mars…”

bringing her to the conclusion that

“based on what I have already read, I can make a general prediction that the main character, Mark, will survive by the end of the story.”

But I personally think that The Martian‘s message is not necessarily about whether Mark Whatney will or not survive his mission. I’ll get more in touch with what Andy Weir is trying to communicate in the fourth section, but here I’m going to talk extensively on the cultural codes present in The Martian to give us a strong sense of, now that we know what the genre is, what Weir is doing with genre.

First we start with Mark Whatney. As I write on the cultural code

“Reading the story I find certain codes. For one Mark Whatney does not have the composure of a stereotypical scientist. He often makes off-color jokes, curses when angry, and acts genuinely emotional in ways coded for a sympathetic under-educated everyman than a loyal scientist and intrepid explorer. At the same time he’s coded as an underdog as well, experiencing several failures and realizing his own slim chances for survival while never given up and always trying for solutions. “

And why is he defined in this way, to be palatable of course. Most of the audience reading The Martian won’t be scientists, so an everyman character such as the underdog is needed, but it goes deeper than that. Andy Weir wants to, as I’ll explain later, to show us a human presence on Mars and he wants us to care.

Building off what I cited Alexis as stating earlier about the proairetic code, Weir is building up throughout the book to Whatney’s survival throughout the book, what with as each problem occurs a solution is presented. In other words, Weir wants to show us Watney’s success, and given his mission on Mars as well as him being representative of a NASA astronaut, he is showing a scenario where NASA successfully (though not without incident) has a successful mission to mars and is trying to persuade us, the audience, that NASA really is something to invest in. Because success does equate to viable in the eyes of the reader. I’ll go more into this in section four.

As for the Semic Codes, there is much to say as for the norms and structures of The Martian. For one Mark Whatney’s habit for appealing to the reader in what we assume are audio-diaries are always accompanied by cursing and lingo. For example

“Things aren’t as bad as they seem. I’m still fucked, mind you. Just not as deeply. Not sure what happened to e Hab, but the rover’s probably fine. It’s not ideal, but at least its’s not leaky phone booth. “

These sections reaffirm the cultural code of Whatney as uncultured, frank, and direct. From cursing at each failure (as he does above) to using as short-hand for a scientific distance formula named “Pirate-Ninjas” Whatney seems to joke or curse each time something bad happens to him, in a way reaffirming his sanity when later he solves the problem he once was cursing about.

Section four

This brings us to the narrative audience. What, in the end, does Andy Weir wish to convey and who is he conveying it to? As I state in one of my own blogs

“Weir’s audience, in a way, cares about the science and is able to digest the scientific bit to understand how amazing what Watney does is and ultimately how it’s doable. “

In other words, Weir intends his audience to care about the “science” elements of the story with his ultimate goal is (as previously stated) to convince his audience that NASA is viable and that in conclusion, a Mars mission is viable.

With the cultural codes I mentioned in the previous section, Weir has been predicting his readership. As stated, Watney is an “everyman” in that rather than having the qualities of a logical academic that puts all his faith in science. Most importantly though…Watney is a joker, a sort of “class-clown” character. For example when relating his plans to rehabilitate his own refuse to use as fertlizer,

“…Being completely desiccated, this particular shit didn’t have bacteria in it anymore, but it still had complex proteins and would serve as useful manure. Adding it to water and active bacteria would quickly get it inunudated, replacing any population killed by the Toliet of Doom”

We see hear not only casual speech (such as the use of the expletive “shit”)

So it can be safe to assume that Weir is targeting the same sort of audience who usually watch American action movies, the non—professionals who often see a movie to see action scenes and explosions. This is clearly evident in the constant explanation of science, since Weir expects the reader to be uninformed, but at least willing to learn. For example

“According to NASA, a human needs 588 liters of oxygen per day to live. Compressed liquid O2 is about 1000 times as dense as gaseous O2 in a comfortable atmosphere. Long story short: With the Hab tank, I have enough O2 to last 49 days”(106).

These sorts of fact are prevalent throughout the book and Weir expects his uneducated audience to follow the science involved in his use of laymans terms. However he is not effective in this capacity, as Laura states when reading over the aforementioned quote “I feel as if I just glanced over times like this in the text. This is supposed to be a vital moment in the book and I feel as if the author was repeating multiple times how this man is trying to survive. I could not keep an interest and, as a reader, I was not being ethical to the author at all in this novel. “

Thus as stated, although a layman or lowest denominational everyman is the target audience of The Martian there are resistant readings that my groupmates suffered throughout the story. Thus there is a gap in my reasoning, in that I have myself proved that although Weir intended his book to target the “average” person my groupmates being unused to the Science-Fiction genre were unable to receive the message of the book. As Alexis states “I had expected it to be really scientific and full of technical terms that I would not understand and because of that I would not enjoy the book because of those aspects. Those were my projections going into the book, and they were justified rather than being wrong as I started reading further into the story. “ Alexis therefore felt that the technical terms and the focus on them made the book difficult for her to read and delve into.

So who is the narrative audience…? I’d like to point to the book “The World is Flat” a book that I was recommended as a teenager which was a layman’s term book on globalization economics. The book expects the user to be unfamiliar with the internet and how it works, and thus goes into in depth explanations of many modern technologies and practices from the ground up. I found the book incredibly dull, but still very well written given its context, because I simply was not interested in economics. Thus I state that Weir intended the reader to not only be a layman, but willing to put in the effort and tolerance to understand the scientific aspects of the books to in turn be “taught” by Weir how NASA and a Mars mission are not only possibilities, but worthy goals. For many of us we simply weren’t interested enough in the concept, I know for me I found the stuff incredibly interesting and was able to finish the book in record time. In terms of mimetic, thematic, inter-textual and narrative the book delivered for me, mostly because I was able to become the audience the author expected me to be.